PolyTrack Physics: The Hidden Complexity of Low-Poly Racing

At first glance, PolyTrack’s minimalist, low-poly aesthetic might suggest a simple arcade racer. However, beneath the hood lies a surprisingly nuanced physics engine that rewards drivers who understand the underlying mechanics of motion, traction, and inertial stability.

True mastery in PolyTrack isn't just about reflexes; it’s about becoming a 'kinetic strategist.' This guide moves beyond the basics to explore how momentum, grip budget, and load transfer dictate your performance on the leaderboards.

The Inertial System: Momentum as Your Primary Resource

In PolyTrack, speed is more than a number—it’s a representation of stored energy. Because the engine prioritizes Newtonian motion, the most important rule is that momentum is expensive to gain but easy to lose.

Unlike arcade racers that allow for instant recovery after a wall tap, PolyTrack’s simulation of conservation of momentum means that every collision redirects or dissipates your kinetic energy. Understanding this turns every corner into a calculation: how much speed can I carry without exceeding the car's structural or frictional limits? Top-tier players don't just 'take turns'; they manage a continuous flow of potential and kinetic energy.

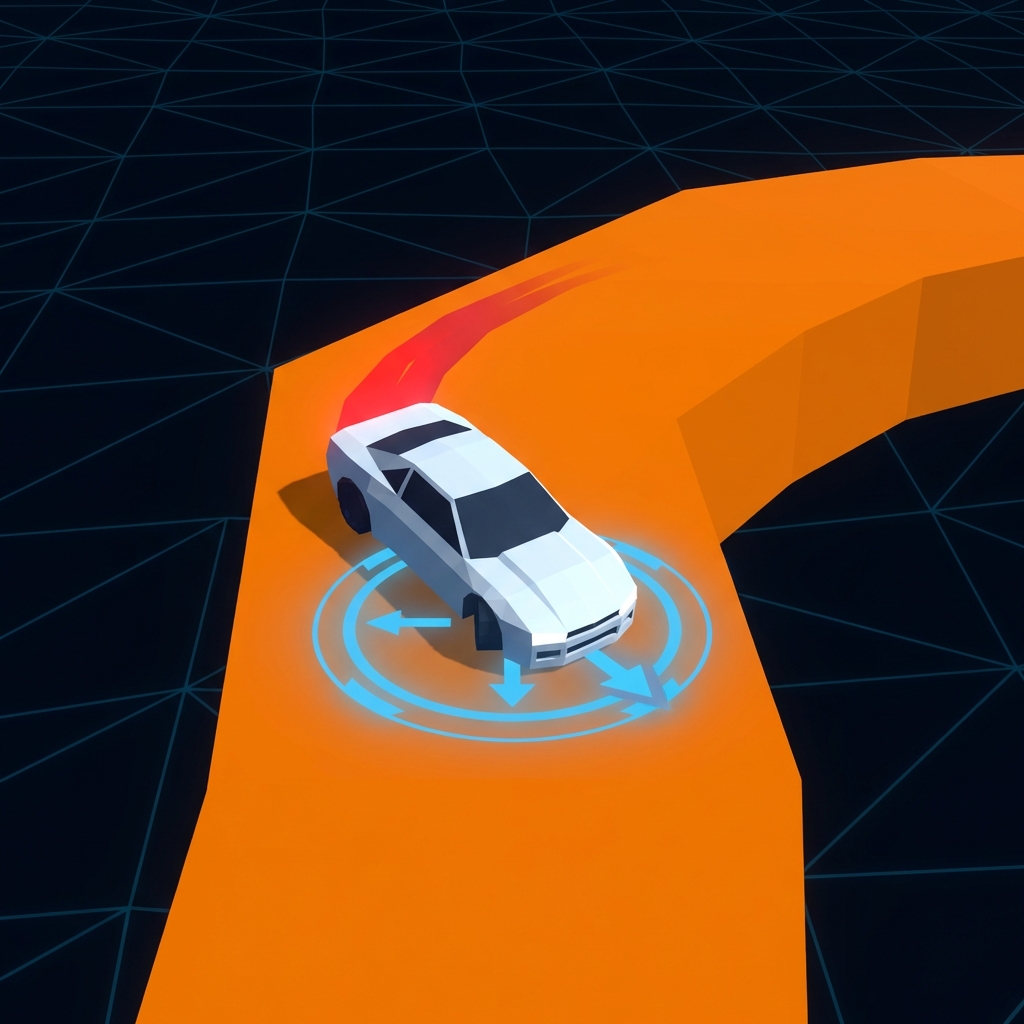

The Friction Circle: Managing Your Grip Economy

The most critical concept to master is the Grip Budget. Your car’s contact with the track is finite. Think of grip as a standard circle: if you use 100% of your tires' capability for acceleration, you have 0% left for steering.

This 'Friction Circle' explains why accelerating hard out of a tight corner often leads to understeer (the front wheels slipping). To optimize your line, you must learn to transition between forces. This involves 'trail-braking'—gradually easing off the brakes as you turn into an apex—allowing the grip budget to transition smoothly from deceleration to lateral cornering force.

Surface Dynamics

Surface coefficients further complicate this economy. Standard tarmac provides a 100% baseline, while boost pads—ironically—often reduce effective grip to roughly 80%. This is why the car feels "jittery" or unstable over boost sections; the increased velocity is fighting a diminished frictional limit.

Load Transfer: Car Attitude and Balance

Your car isn't a static box; it’s a dynamic platform that pitches and rolls. Understanding Weight Transfer is how you manipulate grip on demand.

- Under Braking: The car's nose dives, shifting weight to the front wheels. This increases 'turn-in' bite, making the car more responsive at the start of a corner.

- Under Acceleration: Weight shifts to the rear, planting the rear tires for maximum exit drive but lightening the front, which can cause the car to push wide.

- Lateral Loading: In high-speed sweepers, weight moves to the outside tires. If the turn is sharp enough at high velocity, the inside tires may lift, effectively halving your turning grip.

Mastering weight transfer means anticipating these shifts. By braking slightly before a turn, you plant the nose and prepare the car to rotate. Constant, smooth inputs keep the chassis stable, whereas sudden 'on-off' throttle behavior mid-corner upsets the balance and triggers unrecoverable slides.

Flight Dynamics: The Art of the Perfect Landing

PolyTrack’s aerial sections are where many runs are won or lost. In the air, your car follows a parabolic trajectory determined entirely by your takeoff vector. While you can't change your velocity mid-air, you can—and must—manipulate your Attitude.

The goal is always ** Slope Matching.** If you land on a flat surface, the vertical energy of the fall is absorbed as 'shock' (wasted energy), leading to a massive speed penalty.However, by using the W and S keys to align your car’s pitch exactly with the downward angle of a landing ramp, you convert that vertical fall back into forward horizontal momentum. A perfect landing doesn't just 'feel good'—it’s a literal acceleration boost.

Exploiting the Edge Cases: Speedrunning Physics

For the competitive elite, PolyTrack’s physics engine has several 'undocumented' quirks.

- Angle of Attack at Walls: Shallow-angle collisions (under 20 degrees) often result in a 'grind' rather than a bounce. In certain technical sections, 'scuffing' the wall can actually be faster than a deep-braking line, as it uses the wall as a lateral stabilizer.

- Corner Clipping: Hitboxes for track barriers are often slightly more lenient than their visual models. Understanding where the 'true' physical edge lies allows you to shave millimeters off every apex.

- The Boost Fade: Boost pads don't just stop; their effect tapers off over 2-3 seconds. Chaining pads so the next one hits during the 'fade' of the previous one allows for an additive effect that pushes the car toward its absolute terminal velocity.

Conclusion: The Thinking Driver’s Advantage

Ultimately, PolyTrack is a game of theory as much as execution. When you begin to view every track not just as a series of obstacles, but as a map of gravitational and frictional forces, your driving will naturally evolve.

The best drivers don't just have the fastest fingers—they have the deepest understanding of the 'Inertial Ballet.' Take these principles to the track, experiment with your entries and exits, and treat every crash as a data point in your journey toward mechanical mastery.

Ready to apply the theory?

- Benchmark your grip on our Medium Tracks.

- Test your air control on the Stunt Collection.

- Join the discussion in the community and share your physics findings.

Drive smart. Drive fast. 🏎️🧠